For Mr and Mrs Joplin, it was a different experience. For Laura, who had just graduated from school, and Michael, then 14, it was “mind-blowing” to tour Haight-Ashbury with their big sister and see her perform with Big Brother at the Avalon Ballroom. In the talismanic summer of 1967, the family made the long car journey to visit San Francisco and see Janis at home and, as it were, in action. But our parents supported us – if you wanted to make music or art, go for it”. If you wanted to work at the oil refinery, that was fine. Michael remembers that move as “the logical progression. Janis stayed in touch with her family after she moved to the West Coast in pursuit of her musical dreams. So there’s a sense of her vitality whenever I look at it.“ I remember her working on that scrapbook in her bedroom, cutting things out and doodling. Janis’ scrapbook told you a lot about what she valued, what was important to her, what gave her joy. “That may have been a reflection of our mother – she chronicled our lives on photo scrapbooks. But after a while it became obvious that it was something of not just interest but importance.” And we never felt like sharing that personal, gut-wrenching family thing.

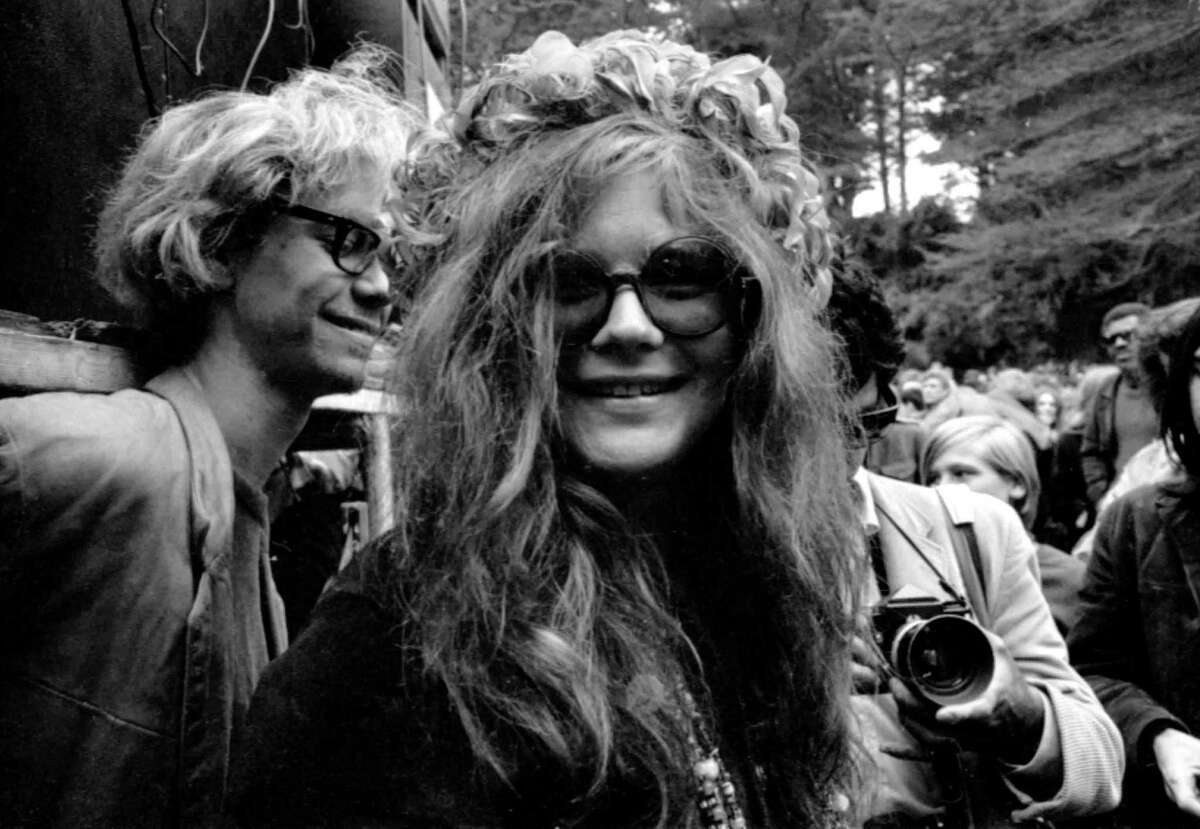

“Janis’ scrapbook has been a personal family thing for such a long time,” says Michael down the line from Arizona, “and we’d all looked at it, and laughed and pointed and wondered and cried. As Kristofferson describes her in his afterword, which comes in the form of a poem titled Epitaph, this was a woman “born so black and blue”. Harder to divine is the darkness inside that compelled Janis to overindulge to the extent that it killed her. This is a deeply personal, kaleidoscopic, hippie-vivid portrait of a woman finding her way in the world, and a window into the dizzying contours of America in the mid- to late-’60s. She gave us a voice that was anti-establishment, and I’ve lived by it ever since”. To quote Hynde, who saw Janis perform in Richfield, Ohio, “there was just no one else like her – total rebelliousness, abandon, musical excellence and total connection with everyone in the audience. Janis Joplin circa 1962 in her hometown of Austin, Texas. “Instead of being the person who had reached the greatest visible recognition in the country, Janis got a tyre for having travelled the longest distance.” “That’s what I find most insulting,” says Laura, audibly pained 51 years later. At the reunion, Janis was symbolically gifted a tyre, to represent “that she’d come the furthest”. It was only when the president of the class said ‘What about Janis Joplin?’ that everyone stood up and applauded.”Įven then, the recognition was miserly. “However, the guy running things thought in terms of how many people had law degrees. But in my mind, and in Janis’, they should have made her attendance and her success one of the central points to celebrate – ‘Look what someone from our high school has achieved!’ There was a sense they didn’t quite know what to do about her.

“Everyone else was in straight, middle-class clothing and teased hair. She accompanied Janis, six years her elder, to the reunion, and wore a dialled-back version of her sister’s fabulous freak-out garb. “It was a formal event and it was an awkward fit,” recalls her 72-year-old sister, Laura, laughing. But before that, there was the detour back to Port Arthur, the small, conservative Texan community in which, as a beatnik-channelling teen rebel, she’d never felt at home. Later that summer of 1970, Joplin would begin work on her second solo album, Pearl.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)